Female Gaze on Uzbekistan's Traditional Barbershops: the Sartaroshxona

Written by Zumrad Mirzalieva, edited by Evar Hussayni

For centuries Uzbekistan has been a hub of cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity, making it a veritable melting pot. The region's cultural diversity is reflected in its various languages, including Turkic and Persian, among others. The different religions that have taken root in Central Asia, such as Islam, Buddhism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism, have each played a significant role in shaping the region's unique cultural landscape. Yet now the predominant religion is Sunni Islam. The discourses that revolved around the region changed over time. According to a researcher Cengiz Sürücü, Central Asia was first recognised as a distinct region of study when it became a key battleground in the Great Game between Russia and Britain in the 19th century. During this time, administrative officers, spies, scientists, linguists, and military officers produced writings that depicted the region as dangerous, dark, and wild. Sürücü asserts that it was during this period that systematic knowledge production on Central Asia began to take shape. Later in the second half of the 20th century and up until the turn of the 21st, the discourse shifted towards an orientalist perception. The region was being recognised by Western scholarship as exotic and attractive. Today, 32 years after the dissolution of the USSR that Uzbekistan was once a part of, the country is still merely regarded as a Post-Soviet country due to the very prejudiced interest in the region. Nonetheless, the reality on the ground is much more complex with multifaceted identities.

Historically there has been a sharp gendered division in the access to public spaces in Uzbekistan. Traditionally, in this gender-segregated society, public space which are inherently associated with politics and power are reserved for men, while women are largely limited to be within their private realm, such as her house or her neighbourhood, feeding into the gender stratification in the region. The extent of mobility a woman has is determined by the type of work she does; therefore, mobility and gender roles are intertwined. For instance, women naturally have greater control over their house than men, meaning that men are often constrained to enter some parts of the house if other women are present.

Nevertheless, despite the limitations, women continue to play critical roles within the community. Despite being circumscribed, women are not victims but rather they exercise agency in appropriating, negotiating and using public spaces. For instance, the inability for women to go to mosques transformed into a grassroot self-formed female groups of religious teachings. In addition, one of the spaces which are actively used by both men and women (however separately) are hair salons. Given that women have very limited access to public spaces, beauty parlors hold a significant importance. By being constantly confined within their homes, beauty parlours act as safe spaces, where emotional and mental health can grow and thrive with a continuous interchange of experience with other women. Considering the patriarchal context and limited resources, traditional mental health assistance is unavailable in most regions of Uzbekistan, therefore, beauty parlours give women a much-needed opportunity to fill-in that void and gather to vent and seek refuge.

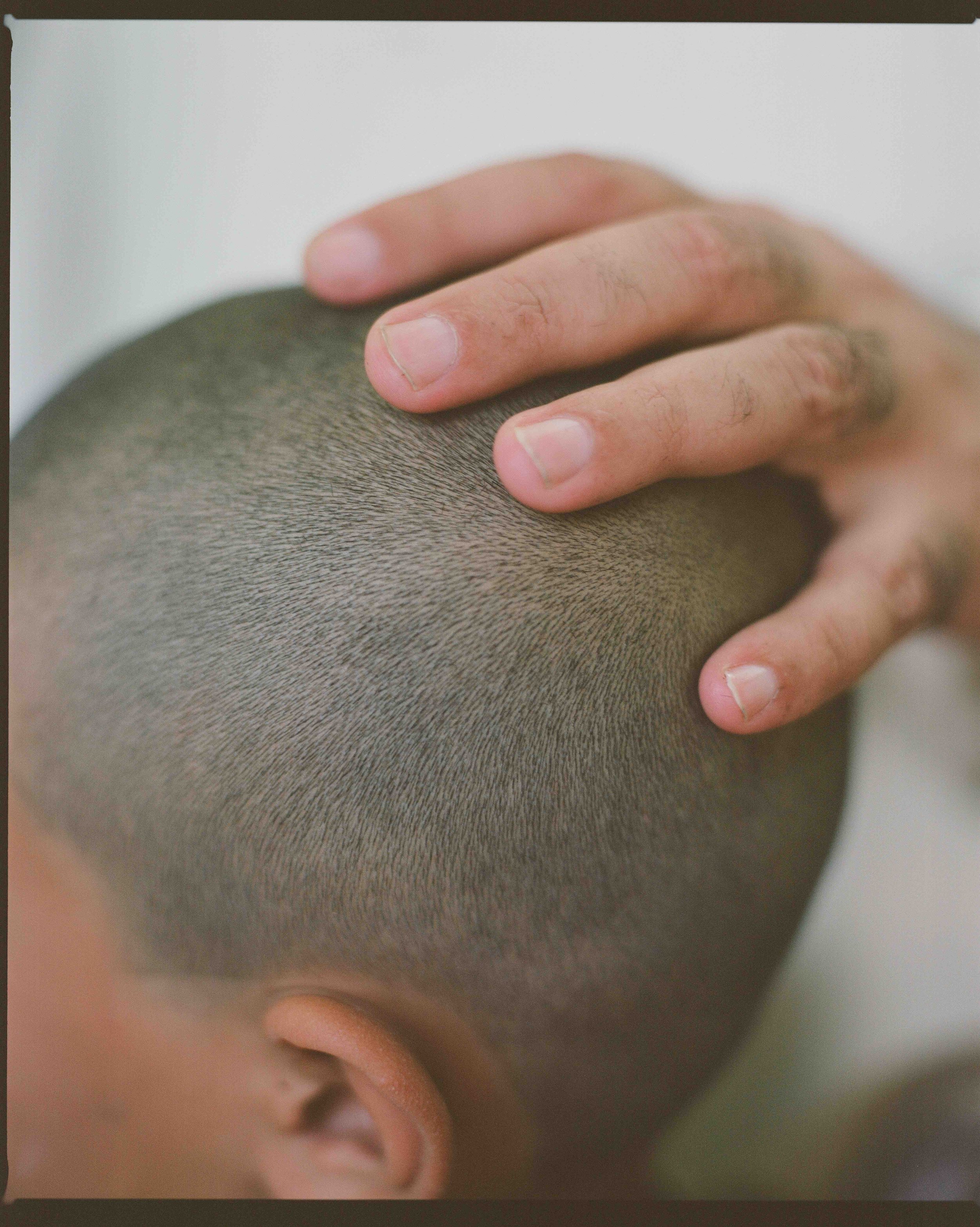

I started my on-going project Sartaroshxona (translated from English as barbershop) in 2021 with the aim to firstly allow myself into the male-only spaces that are traditionally unavailable to women and explore whether the cultural dynamics in Sartaroshxona’s are similar to those in female-only beauty parlours in order to challenge the existing gender dichotomy. During my work, I was fortunate enough to have my partner accompany me throughout the journey. The presence of a man representative gave me more credibility and actually provided access to the barbershops in the first place. For instance, it was my partner who would enter the barbershop first and ask permission from the barber and the clients for me to take photos. The majority would agree although a slight hesitation was still present. Nonetheless, the ‘staged’ hint of the finished work serves as evidence that throughout the whole process there were great collaboration efforts between us. Each barber later received a printed copy of their portraits which are now proudly displayed in the barbershops in various corners of the country.

Given that Sartaroshxona’s are environments where only men go, it could be considered that they are spaces in which identities are manifested, projected, shaped and negotiated through the establishment of certain ideas of masculinity. They are of particular historical importance to the communities, as they act as time-honored cultural institutions, where often the expertise of a barber is translated from one generation to another. The capacity of Sartaroshxona’s go beyond mere grooming purposes, rather it is a space for men to socialize and discuss important topics, given the restricted availability of social spaces which are often limited to teahouses (choyxonas’) and bazaars. The social dynamics that take place in the barbershops have helped to create a sense of camaraderie and community that is unique to these spaces. Therefore, it is especially interesting to observe the similarities with the dynamics in women-only beauty parlours. Not only do they serve the similar purpose in terms of improving one’s appearance, but most importantly both serve as a community space for men and women.

Finally, globalisation and Western cultural hegemony put this cultural code at risk. Over the past several years, Sartaroshxona’s are being gradually replaced by modern, almost identical barbershops; therefore, it is especially important for me to start this project now. More and more Sartaroshxona’s are now being called “barbershops”, a word completely unfamiliar to our culture. The loss of Sartaroshxona represents more than just a change in architecture and style; it signals the erosion of a distinct cultural code and a way of life that has been passed down from generation to generation. The rise of western-style barbershops and the use of unfamiliar terminology threatens to erase the unique cultural characteristics that have long been associated with the traditional Uzbek experience. It is why documenting the Sartaroshxona and starting this project was so important to me.

Credits: Thank you to Ilkhom Ikramov (my partner and biggest supporter). Thank you to the barbers: Farkhod, Komil, Zoir, Jamshid and Shamsiddin.

You can find more of Zumrad’s work on @zuma.mir