Pride and Politics as an Iraqi woman: how losing a brother and being raised by feminists can shape you

“If you were to lose a brother, and watch the rest of your family become displaced as refugees, your identity would become political too”

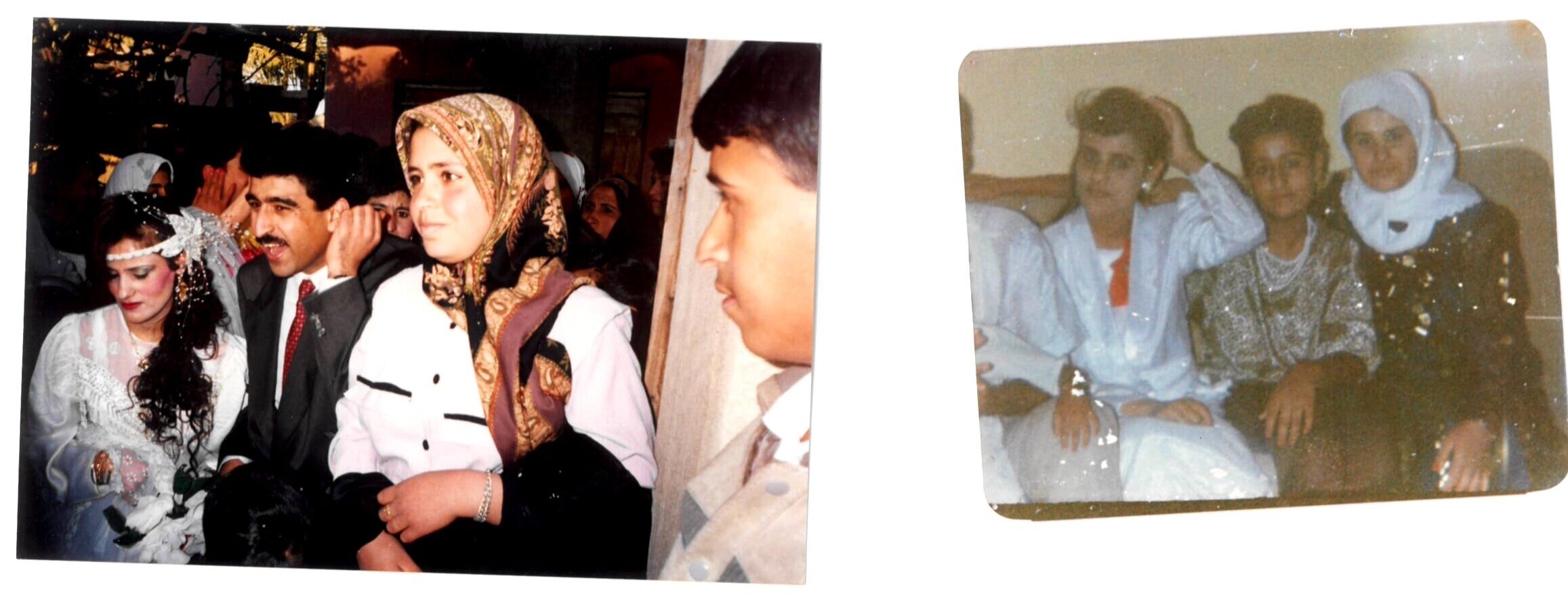

Family photos by Mariam Abood

Words by Mariam Abood, edited by Shayma Bakht

My identity is something that I have always had an arduous relationship with. I have a dual identity. I am British, but I’m also an Iraqi - and a proud one at that. Yet, despite feeling pride in my roots, I also feel the need to hide my heritage when entering political spheres.

My secretive nature stems from trauma in my childhood. My parents always took pride in our heritage and told us to share it widely. So, that is exactly what I did. At primary school, I would exclaim how proud it felt to be Iraqi. But, this was met with disgust from my classmates. I still remember a white girl at school affronting me, telling me I was “responsible for the death of British soldiers”. As a young girl, I felt embarrassed and ashamed. I became self-loathing and disgusted. At that moment, I detested being Iraqi. I realised it made me a spectacle and a target for harassment.

Mariam and her family in Iraq. Photos by Mariam Abood

This dehumanising experience stuck with me throughout my life and made me resent my heritage. I stopped speaking Arabic. I did everything in my power to make people see me as British. However, my skin colour meant I could never be enough. I am “othered” by my peers, the media, and the public. This is not helped by tainted representations of Iraqis on television and in film.

I found it disturbing how Hollywood would inaccurately portray Iraqis as terrorists. The sad reality is that your average person living in Iraq does not even have access to clean or safe drinking water - let alone weapons of mass destruction.

I realised being born in Britain doesn’t change the fact that I am brown and dark-skinned. This is inescapable when I hear racial slurs shouted at me in the street. I have been called a “paki”, a “darkie” and I’ve been told to “piss off back to wherever I came from”.

These issues with my identity only worsen when I enter politics. I find my heritage is always politicised by others. White men ‘mansplain’ my own history to me, and I am told that Arabs, like me, “need to be displaced from Iraq for any hope of peace in the region”.

Despite Britain’s hypocritical insistence on having statues of slave traders honoured across the country, which serve as visual representations of Britain’s racist and violent past, I am often told that it is us, Arabs and Iraqis, who should feel ashamed for the disquiet within our home countries.

White men have told me that Arabs create the tension in Iraq, when the root of the problem lies in the Sykes-Picot agreement and all who perpetuate its infamous colonialist legacy in the Middle East. For those who don’t know: the Sykes-Picot agreement was, in essence, French and British governments drawing random lines in the sand to dictate the borders of modern-day Iraq. This agreement was followed by civil unrest and a failed monarchy. It became the starting point of decades of bloodshed. Bloodshed that my family witnessed first hand.

My brother suffered from Ichthyosis, a pre-congenital skin disorder. He lived in Iraq and was seeking treatment in his home country. What people do not realise about war, is that there are many fatalities to airstrikes that are both direct and indirect. During the bombing campaign, which targeted schools and hospitals, his local hospital was destroyed in the bloodshed, meaning my brother could not seek appropriate treatment for his condition. He died as a result.

These destructive colonialist lines were built upon by US Bush administrations, who purposefully made the divide between the Arabs and the Kurds larger, so they could justify invasion and propagate their own agendas. I find myself constantly explaining and arguing my own history to people all the time. It is an exhausting process. I feel demonised and dehumanised while having these political arguments.

Just existing as an Iraqi woman means I have a duty to speak on behalf of a nation. British women from minority ethnic backgrounds feel the need to speak with urgency on these topics due to the unapproved politicisation of our identities. Too often the British narrative on Iraq causes the West to forget we are human too.

Mariam’s feminist mother. Photo by Mariam Abood

Growing up, I remember seeing some positive backlash against the Iraq war. I was humbled by the number of Britons protesting against Bush and Blair’s invasion. My father travelled to join the protestors and even met ex-London Mayor Ken Livingstone. However, even then, I found my country and my identity was - once again - politicised to serve the agendas of others. Were people pretending to care about Iraq and our people just to criticise then-Prime Minister Tony Blair?

I cannot put all the blame on others because I unconsciously politicise my identity too. When your family experiences war, you cannot help becoming political. When the Bush administration targeted schools and hospitals with a bomb campaign in the Gulf War, those who were already sick, like my brother, perished.

If you were to lose a brother, and watch the rest of your family become displaced as refugees, your identity would become political too. Regardless of how I feel, I cannot help but be politicised, as politics continues to shape my existence.

I was raised by an army of feminists who taught me to advocate for Womxn’s rights and education. My own mother, who is a Gulf War survivor, was one of many brave Iraqis who ran women’s education programmes amidst conflict. They were the first in their families to take action and try to end female illiteracy in Iraq. This is often forgotten by Western feminist movements.

Despite all the pain, the legacy of Iraqi women makes me take the greatest pride in my heritage and identity. In the end, it makes me proud of my roots.