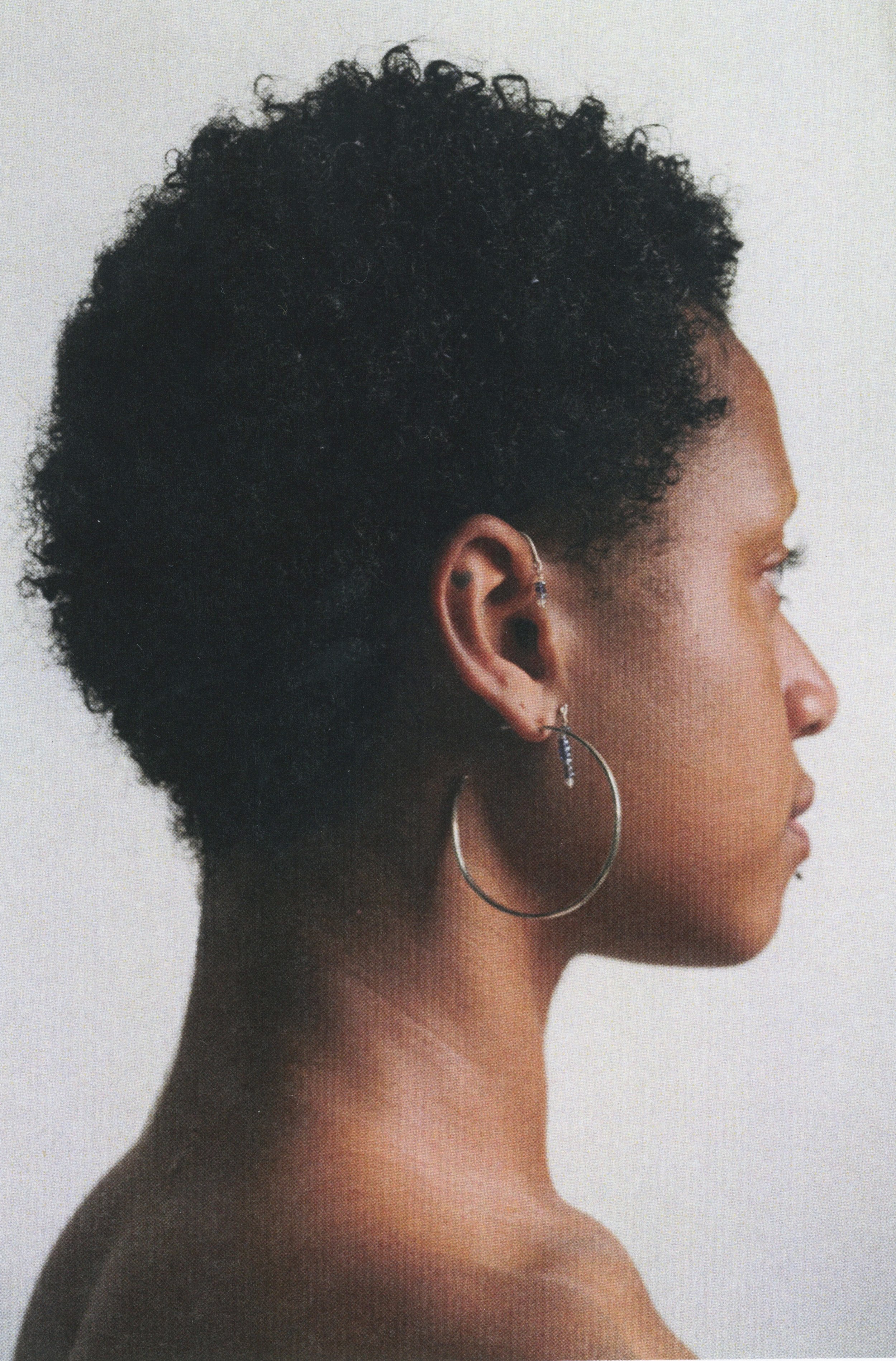

N9CRA: Silver work reflective of the moon, the ocean and ancestral practices of adornment

Interview and words by Jameela Elfaki

Introducing N9CRA, a collection of unique silver work by Moroccan-Iranian artist Camelia Chorsi. N9CRA (nuq-rah) is the Moroccan Darija Arabic word for ‘silver’. Similarly, the Farsi word for silver is ‘noughre’. Camelia explains that both signify where the moon meets the water.

When I was first introduced to Camelia’s work, I instantly fell in love with it – having a very similar deep appreciation for silver jewellery and its unique qualities and cultural significances. I knew there was something really special and exceptionally unique about the approach, concept and craft of Camelia’s work. It wasn’t just jewellery, it was silver crafted with the ancestral qualities, histories and traditions in mind, crafted with love, purpose and a deeper intent to honour tradition whilst creating something new. Camelia believes she has a responsibility to preserve the craft and the joy of ornament/adornment in North African and Iranian culture. By using silver as a material to create jewellery, she aims to reflect and protect our inner energies.

“In Moroccan history, amongst the Amazigh and the Touareg, silver jewellery held exactly this purpose— to protect women from negative energies, and to identify them as belonging to their tribe or to their husband. As I looked deeper into the material properties of the silver element, I learned what a powerful metaphysical energy it held. It is one of the most reflective elements on our Earth— a protector for reflecting away negativity. It is a healing element believed to have antibacterial properties — a purifier.”

Camelia gives us a deep insight into her own artistry, the metal work traditions and the rituals around N9CRA, with hope that we can better understand our own cultural histories of adornment and connection to ancestral practices.

AZEEMA: Could you tell us more about yourself, your background and where you are based/grew up?

Camelia: I was born in Miami to an Iranian father from Khoy and a Moroccan mother from Fes. I lived my early childhood there before moving back to Casablanca, where my mother’s side of the family is located. Several layers of displacement have led me to experience a dissonance in understanding my true self and desires, and the freedom to embody that manifestation in different spaces. I have found that my form of healing is in liberating the unconscious and allowing the experience of true feeling to be communicated to myself and others. Through imprints, our environments create distance between us and this natural line of communication. I feel the responsibility to assess how cultural values are transmitted to support this search for home and the true self– to heal and to remind ourselves.

I saw a beautiful piece written with you and your work about nostalgia and rituals. What inspires you as an artist? How do your work and your heritage intertwine?

I create to fulfil the responsibility of being within this body, for the privilege of giving, and to share stories of my truth. I understand that the deepest expression of a personal truth becomes universal. In this lifetime, I am in a constant search for freedom. I question how it is experienced through bodies across spaces, and how these experiences of freedom are ritualised and translated across cultures. I am a healer exploring the collective unconscious, making works through movement in many forms.

I am inspired by lost stories that are felt and found in the collective. These stories are the same lessons that we already know and need to be reminded of. I believe that our deepest sense of understanding is already within us. We build experiences to reconnect to our culture, beliefs, and love. We calcify layers onto our vessels over time just to crack them and re-discover our deepest desires.

I have also been inspired by the ways we translate rituals of freedom: the experience of home through the body, the contradictions of culture and love, and of freedom and fear.

North African and Iranian women deal with similar struggles surrounding the basic act of expression that I address in my practice. As connected as we feel to our homes, it is difficult to feel at home within our bodies. Part of this weight can be traced to our post-colonial gender constructs, as well as where we feel capable to receive and respond to our socio-cultural ideologies. When I am shamed, am I allowed to respond? When I am proud, am I to feel shame? When my worth is in analysis, should I rely on my appearance? When I am told my desires are not valid, should I give up on getting to know myself?

“It pains me that traditional forms of craft are continuously lost from the hands of our elders. These traditions have had to shift to make way for styles that would appeal to tourism to sustain themselves.”

As an artist with multiple practices, what drew you to jewellery specifically?

I come from a lineage of craftsmen and artisans through both my Moroccan and Iranian ancestry. My grandfather in Khoy, Iran was a khayyat who made clothing and opened his store in his hometown. My grandmother in Fes was also a khayyata who made Kaftans before entering the world of aestheticians — the craft of bodily self-care in appearance. Her mother specialised in making the s9alli embroidery for Kaftans. My great grandfather specialised in making les taboureh: leather poufs hand tinted, sewn, and embroidered. He would make a pair each month.

It has always been my nature to work with my hands. As I gain new skills, I realise I am learning what my hands already know. Whether that’s in making shoes, clothes, painting, drawing, or sculpting.

Jewellery is my favourite form of wearable sculpture. It gives us the opportunity to adorn ourselves with the history of our belonging and with the strong energy of our chosen metals and stones.

It pains me that traditional forms of craft are continuously lost from the hands of our elders. These traditions have had to shift to make way for styles that would appeal to tourism to sustain themselves. Within both cultures, we have grown more interested in Western adornment, not understanding the value of our own material histories.

My interest in making silver jewellery began as an extension of the practice of my ancestors. I share the responsibility to preserve the craft and the joy of ornament in North African and Persian culture.

“[Silver] is the metal reflective of the moon and the ocean, aligning us to the divine feminine, or anima, particularly sensitive to the full and new moons.”

Could you explain the name N9CRA? What does it mean and what is the inspiration for N9CRA?

I have always been drawn to silver jewellery — as many rings that could fit on my fingers and as many links that could hang from my neck. I felt as though they served the purpose to protect me, as well as a means of reclaiming my body.

In Moroccan history, amongst the Amazigh and Touareg, silver jewellery held exactly this purpose— to protect women from negative energies, and to identify them as belonging to their tribe or to their husband.

As I looked deeper into the material properties of the silver element, I learned what a powerful metaphysical energy it held. It is one of the most reflective elements on our Earth— a protector for reflecting away negativity. It is a healing element believed to have antibacterial properties — a purifier.

It is the metal reflective of the moon and the ocean, aligning us to the divine feminine, or anima, particularly sensitive to the full and new moons. Silver can enhance psychic connections and intuition. Like the waters of the oceans it responds to, it is the metal of emotions — regulating our inner tides and enhancing the depth of our feelings. As an energetic conductor, it also enhances the properties of any stone it is paired with.

The levels of metaphysical properties of silver are almost endless. N9CRA (nuq-rah) is the Moroccan Darija Arabic word for silver. Similarly, the Farsi word for silver is ‘noughre’. Both signify where the moon meets the water.

Let's dive into the collection NIYA. Why silver? Could you explain the metaphysical and ancestral elements to the collection?

Through the jewellery I make, I wish to reinforce our material relationship to the pieces we choose to adorn ourselves with. NIYA is the Arabic word for intention. By maintaining the intention with everything we allow into our energy, we can create conscious harmonies.

NIYA is created and worn through collective intention — the commitment to the energy we adorn ourselves with. With a responsibility to the wearer, the pieces in this collection establish a material relationship between silver, stone, and the body. The choice of stones in this collection focuses on intuition, vision, inner knowing, transformation, truth, and protection using Labradorite, Iolite, and Pearl.

This collection was born while visiting my father’s farm in a village called Otursara, located in the Gilan Province of Iran. I spent several months there in the past two years harvesting, painting, writing, and re-connecting to the land.

That is where I understood the intention behind my process, and how elements come together to give it life.

Was this a spiritual process making the jewellery? I think there are deep tangible connections with ancestry and the earth.

I believe that thoughts and ideas derive from that which has already been. Our ancestors are whispering to us through the confidence of our creative decisions.

There is no doubt a connection with the Earth in the process of metalwork as our materials are sourced from her womb.

Silver is formed in the crust, and I work with fire to mould her into shape, the same way our ancestors learned how to. Everything resides within the collective consciousness whether we are open to access it or not.

“Attention is shifting to the virtual world where convenience seduces and consumption reprograms our material desires to a Western ideal.”

What is the importance of preserving North African & Iranian practices through your craft?

In preserving North African and Iranian methods of making, the value of skill and craft is maintained in homage to an extensive history where materiality meets ritual. The material properties are rich in their purpose and embodied through rituals of adornment — rooted in the union of partnership, identity tied to community, and the aesthetics of beauty.

In this sense, the act of preservation channels the original relationship between people and material, in order for the root purpose to be understood and re-discovered, and for this relationship to be respected and maintained. Cultural practices in craft are diminishing from our modern consciousness. Attention is shifting to the virtual world where convenience seduces and consumption reprograms our material desires to a Western ideal.

If you would like to see more or Camelia’s work, you can follow her here. And visit N9CRA’s website here.